CWTS Article of the Month!

Fall 2014

"Hill the Barber OH-165BWa"

by John Ostendorf and David Zimmerman

Listed by the Fulds as OH-165BW-7 through 10, it is fairly obvious that these varieties were issued by a barber and not by Dr. Hiram H. Hill, the druggist who was the issuer of OH-165BW-1 through 6. Thus, I suggested the separate listing of OH165BWa in my book, Civil War Store Cards of Cincinnati. However, I still didn't know who the issuer of the Hill the barber tokens was at the time.

My friend David Zimmerman helped with a key piece of information that was right under my nose (and even published in my book). In the 1862 city directory for Cincinnati we have the following listings:

- Hill, Wm, Barber, 32 Central Ave.

- Rouse, Ellis, Barber, 32 Central Ave.

|

Readers may recognize that Ellis Rouse was the African-American issuer of tokens listed as OH-165FB. I will present in a separate article that all Civil War tokens issued by barbers were issued by African-Americans.

To put it mildly, it was not easy being an African-American in 1862. In the Southern states, African-Americans were usually slaves. In the Northern states, African-Americans may have been free, but they usually didn't have the same rights enjoyed by most Americans and at best, were treated as second class citizens. They were limited in the trades they were allowed to pursue; but barbering was a trade that was dominated by African-Americans, mainly because whites did not want to engage in a trade associated with servitude.

Cincinnati, just across the Ohio River from Kentucky, was just barely in the northern state of Ohio and African-Americans certainly didn't have equal rights. African-Americans tended to keep to themselves and any partnership would have certainly only been with other African-Americans. So there is no doubt that William Hill was an African-American.

Further support is provided in the 1860 and 1870 census records:

1860 census for Ripley, Brown County, Ohio:

- Rouse, Ellis, 27, male, black, Barber, b. Ohio

- “ , Anna, 27, female, black, b. Virginia

- William Hill, 19, Barber, male, mulatto, Barber, b. Virginia

- M.E. Lucas, 11, female, mulatto, b. Virginia

|

1870 census for Hamilton, Butler County, Ohio:

- Hill, William, 28, male, black, Barber, b. Ohio

- " , Amanda, 24, female, black, b. Ohio

- Rouse, Permedia, 48, female, black, at home helping, b. Kentucky

- Johnson, Ida, 3, female, black, b. Ohio

|

From the census records, there seems to be some sort of familial relationship between William Hill and Ellis Rouse. Due to the shameful impact that slavery had on African-American families, it is often difficult to trace these relationships. Families were fragmented and many sadly spent years after the Civil War trying to find family members that were sold in slavery and taken away. There are many sad advertisements in African-American newspapers in the late 1860s seeking information about 'lost' family members.

Clearly, William Hill was African-American and was associated with Ellis Rouse, the issuer of tokens catalogued as OH-165FB.

Hill also served in the Black Brigade of Cincinnati which worked on defensive fortifications for the city in September, 1862 only months after mobs of white men terrorized the black population in Cincinnati resulting in the loss of life and destruction of property. He was later listed in a draft registration list.

Draft Registration List for Cincinnati, June, 1863:

- Hill, William, 20, colored, barber, b. North Carolina

|

Based on the forgoing, the store card committee chose to list the Hill, barber tokens as OH-165BWa.

Citations:

Fuld, George and Melvin,

U.S. Civil War Store Cards, Second Edition, Quarterman Publications, Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1975.

Ostendorf, John,

Civil War Cards of Cincinnati, Lulu Press, 2007. Civil War Tokens of Cincinnati, John Ostendorf.

Federal census for Ripley County, Ohio 1860 and Butler County, Ohio 1870.

U.S. Civil War Draft Registration Records, 1863-1865.

"African American Issuers of Civil War Store Cards"

by John Ostendorf and David Zimmerman

A truly fascinating area of numismatics is a study of early African-American token issuers. At a time when African Americans did not have equal rights, were generally mistreated in the North and enslaved in the South, there were a few pioneering black men who issued store cards in the 1860s.

The very rst tokens issued in the United States by African-Americans were Civil War tokens. It is arguable as to who the rst issuer was, but as I will demonstrate in this article, it was most likely either Charles E. Clark of Cincinnati or McKay & Lapsley of Nashville in 1863.

From the antebellum period until the late 19th century, barbering was primarily a black profession. Also called, "color line barbers", these barbers served only white men and did not allow fellow blacks to patronize their shops for fear of losing their white customers. Barbering was dominated by black men due to an aversion by whites to a trade involving personal service and an attitude by whites that a profession of servitude was appropriate for black men. In fact, every Civil War store card issued by a barber was issued by an African-American.

Barbering was a profession that allowed black men to reach economic levels unachievable in the other limited professions they were allowed to work in. As will be seen in this article, many black barbers became leading citizens in at least the African-American portions of their communities. It is an interesting paradox when considering these barbers had to enforce racial segregation of their own businesses in order to achieve their success.

Many black barbers were actually mulattos, men who had a white father, but were treated as blacks. These men may have had an advantage in that their white fathers freed them and gave them nancial assistance in starting their business. The racial classi cation was not consistent in its usage, so often a person is listed as 'mulatto' in one record and as 'black' or even 'colored' in another record.

It can be safely said that very few 19th century store cards were issued by African-Americans. The following ei ght merchants, four from Cincinnati and four from Nashville, represent the earliest store cards issued in the United States by African-Americans.

Cincinnati issuers:

Cincinnati, on the northern banks of the Ohio River and directly across the Ohio River from Covington and Newport, Kentucky was a city with many southern sympathizers. In fact, many citizens of northern Kentucky worked in Cincinnati and either travelled across the bridge or took a ferry in to work. Slavery never existed in Ohio, but it existed in Kentucky until ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on December, 18, 1865.

There was a general hostility toward blacks in Cincinnati and mobs of white men were known to terrorize the black community in the 1860s. After Confederate raids and Union losses in Kentucky in 1862, Cincinnati prepared forti cations to defend against a Confederate attack. Among those helping in the defense of the city was the Black Brigade of Cincinnati of which two Civil War token issuing barbers were members.

OH-165Y C.E. Clark, Cincinnati, Ohio

Charles E. Clark, operated the Lightning Hair Dyeing Room in the Burnet House, a major hotel in Cincinnati at the corner of 3rd and Vine. He is listed as a barber at this address in the 1860-66 city directories. Cincinnati draft registration records show Clark as a 29 year old 'colored' barber in June, 1863.

Clark's tokens include several that probably circulated during the Civil War. Struck by the Stanton shop, the 1863 dated -2a and -4a varieties appear to have been struck for circulation. Off-metal varieties of both -2 and -4 were also likely struck during the Civil War for sale in the Great Western Sanitary Fair in Cincinnati held from December, 1863 to April ,1864 and were not intended for circulation. Although dated 1863, the 1069 die was in use after the Civil War to produce collector strikes, as was the 1864 dated 1047 die.

The -2a and -4a varieties were probably struck in 1863 and may be the earliest tokens struck by an African-American in the United States.

OH-165BWa Hill, Cincinnati, Ohio

William Hill was associated with Ellis Rouse. ey were both listed at the same business address in the 1862 city directory and census records show a probable familial relationship. William Hill also served in the Black Brigade that built defenses against Confederate attack in September, 1862 along with Henry Porter (OH-165EO).

Hill's tokens were struck by William Lanphear's shop and represent the only African American tokens struck by Lanphear. Hill was last listed as a barber in the 1864 city directory and Lanphear's business closed c.1867. The varieties currently listed as -7a and -8a,'One Shave' and 'One Haircut', respectively, make sense for a barber. The -9a variety, with a $5.00 denomination, and the -10a variety muling were probably collector's strikes. The Hill tokens will be catalogued as OH-165BWa-1 through 4 in the 3rd edition of the store card book.

OH-165EO Henry Porter, Cincinnati, Ohio

Henry Porter was listed as a barber in the 1863, 64, 66, and 67 city directories. He was rst listed at the 95 Fifth Street address on the token in the 1866 directory. Porter served in the Black Brigade of Cincinnati along with William Hill (OH-165BWa).

Porter's tokens were struck by the Stanton shop, probably once the business had been purchased by Murdock & Spencer. It is possible that the Porter tokens were struck after the Civil War.

OH-165FB Ellis Rouse, Cincinnati, Ohio

Ellis Rouse was associated with William Hill Both men were listed at the same business address in the 1862 city directory and Hill lived in Rouse's household in 1860 per the census records. Rouse was also listed in the 1864 directory in partnership with William Brown and in the 1865 and 1866 directories as a sole proprietor.

Rouse's tokens were struck by the Stanton shop, probably once the business had been purchased by Murdock & Spencer. Rouse's tokens may have been struck after the Civil War.

Nashville issuers:

An important shipping port on the Cumberland River, Nashville was the rst confederate capitol to fall when it fell to Union troops in February, 1862. Many escaped slaves, freed blacks, and other citizens migrated to Nashville due to its relative safety under the occupation of federal troops and made Nashville a thriving city during the Civil War. Black citizens helped in the forti cation of the city in late 1862 and again in 1864 prior to the Battle of Nashville which was easily won by Union troops.

Despite the occupation of federal troops, slavery was not eliminated by their occupation nor the Emancipation Proclamation that affected only areas under rebel control. Slavery did not of cially end in Nashville until early 1865, although its practice was minimal by this time.

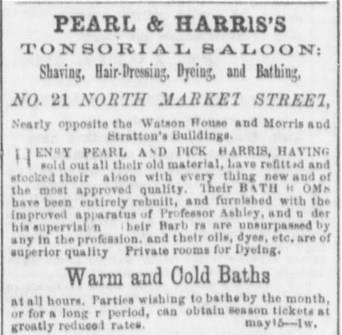

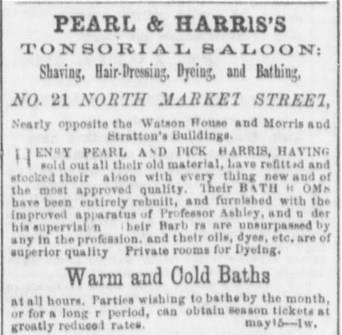

TN-690B Harris & Pearl, Nashville, Tennessee

Dick Harris & Henry Pearl were listed as the proprietors of the Tonsorial Saloon at 21 N. Market Street in the May 20, 1863 edition of The Nashville Daily Union. Curiously, the partnership is listed as Pearl & Harris, not Harris & Pearl as on TN-690B.

I could not find Harris or Pearl in the 1860 census. They were listed in partnership as Harris & Pearl, barbers, 21 N. Market in the 1865-66 Nashville city directories (there were no directories issued in 1861-1864). The partnership appears to have dissolved after 1866. The 1867 directory lists the partnership of Pearl & Merrill, barbers, 32 N. Market St.

The 1870 census for Nashville, Davidsion County, Tennessee has the following:

- Harris, Dick, 60, male, black, whitewasher, born in Tennessee

- " , Sarah, 30, female, black, born in Virginia Pearl, Dilcey, 59, female, black, born in Tennessee

- “ , Henry, 28, male, mulatto, porter in bank, born in Tennessee

- “ , Margaretta, 38, female, mulatto, born in Tennessee

|

The Harris & Pearl tokens were struck by the Stanton shop, quite likely after it was purchased by Murdock & Spencer. All are very rare and several were clearly collector strikes. It is unclear whether any were actually struck during the Civil War.

TN-690C D.L. Lapsley & Co.

See TN-690D. It is unclear when this rm operated. Daniel L. Lapsley was in business with Alfred McKay from 18631870. All of the stock dies used as reverses for TN-690C tokens are known to have post-war usages and were probably struck by Murdock & Spencer. All are very rare and several were clearly collector strikes. It is quite likely that the TN690C tokens were issued after the Civil War.

TN-690D McKay & Lapsley, Nashville, Tennessee

Alfred McKay & Daniel Lapsley appear to have opened their business in 1863.

The following advertisement ran in the December 22, 1863 edition of the Nashville Daily Union:

The partnership is listed in the 1865-1870 city directories. Daniel Lapsley was later a justice of the peace, teacher, and lawyer. He was heavily involved in Republican politics and is mentioned frequently in contemporary newspapers.

As with the other black barber tokens, many varieties were possibly issued post Civil War or were collector strikes; however, two varieties bear special mention. The -1a variety used the 1042 die dated 1863. This die is well known to have been struck by the Stanton shop in a 'triad' of copper, brass, and tin plate as collector strikes for sale in the Great Western Sanitary Fair in Cincinnati in December, 1863 to April,1864. However, this token is known only in copper and the 1042 die was also used for circulation strikes. The -1a variety was almost certainly struck in 1863.

The currently unlisted -12a die used the stock die of a Stanton backstamp. This is important because all Stanton backstamps that can be dated were struck in 1863. Also, Stanton sold his business to Murdock and Spencer in the fall of 1864. Unlike the -1a variety utilizing the 1042 die, the Stanton backstamp was never used for collector strikes. It was a purely utilitarian die. Thus, we can say with near certainty that the -12a variety was struck in 1863.

The -1a and -12a varieties are possibilities as the first token struck by an African-American in the United States.

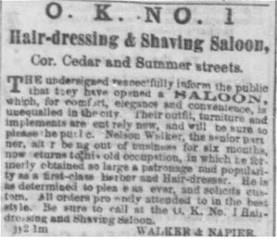

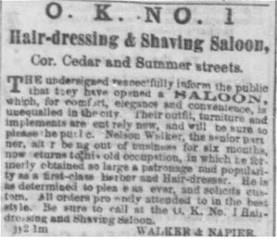

TN-690E Walker & Napier Nashville, Tennessee

Nelson Walker and Elias W. Napier were listed in partnership as barbers in the 1865 through at least the 1870 Nashville city directories (there were no directories issued 1861-1864). They were listed at 28 North College in 1865 and 1866, and then at various other locations in later years. An advertisement in the July 2, 1865 Nashville Daily Union mentions the partnership:

Note that the advertisement was purchased to run one month from July 2, 1865 and indicates that Walker & Napier had only recently opened their business. They were not listed in the 1865 city directory and were listed only in the 1866 directory. It is highly likely that the Walker & Napier tokens were struck after the Civil War by Murdock & Spencer.

Neither man could be found in the 1860 census. The 1870 census for Nashville, Davidson County, Tennessee lists the following:

- Walker, Nelson, 45 male, mulatto, barber, born in Virginia

- " , Elija, 43, female, mulatto, dress maker, born in Tennessee

- " , Salina, 18, female, mulatto, dress maker, born in Tennessee

- " , Virginia, 14, female, black, born in Tennessee

- " , Sallie, 12, female, mulatto, born in Tennessee

- " , William, 10, male, mulatto, born in Tennessee

- " , John, 8, male, mulatto, born in Tennessee

- " , Robert, 3, male, mulatto, born in Tennessee

- Walker, James, 21, male, mulatto, barber, born in Tennessee

- Napier, W.C., 46, mulatto, teamster, born in Alabama

- " , Jane E., 46, female, mulatto, born in Tennesee

- " , Elias W., 21, mulatto, barber, born in Ohio

- " , Alonzo, 29, mulatto, born in Tennessee

- " . Ida M., 12, mulatto, born in Tennessee

|

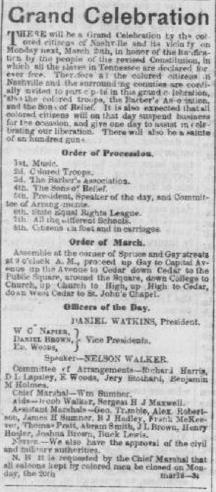

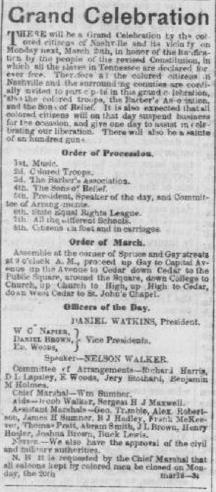

While many of these tokens may have been struck in the late 1860s, it does not take away from the importance of these tokens. They all represent very early African-American tokens. Consider the following announcement that appeared in the March 18, 1865 edition of the Nashville Daily Union. This announcement mentions a grand celebration marking the end of slavery in Tennessee due to the rati cation of Tennessee's new constitution. Note that the 3rd order of procession was by the Barbers' Association. Also note that W.C. Napier (father of Elias Napier) was one of the Vice Presidents. Nelson Walker was listed as a speaker and serving on the Committee of Arrangements were Richard Harris and D.L. Lapsley.

It is amazing to think that the Tennessee tokens mentioned above were all issued by black men within only a few years of the abolition of slavery in Tennessee. Several varieties were issued by black men while slavery still existed and only six years after the dreadful Dred Scott decision in which the Supreme Court basically held that African-Americans were not citizens.

The earliest black barber tokens were issued at a time in which blacks were enslaved in many parts of the country and all black barber tokens were issued at a time in which blacks did not enjoy equal rights with white citizens.

In my opinion, this subset of Civil War store cards is currently underappreciated for what they represent. To truly appreciate what these tokens represent, one must consider the times and conditions in which these men lived. These tokens were issued by black men who were business owners during the Civil War or during the earliest days of the Reconstruction. These men were true pioneers and their tokens represent some of the most important and historical exonumia available to U.S. collectors.

Acknowledgment:

I would like to thank my friend and excellent researcher, Mark Gatcha who rst suggested that the Civil War barber tokens may have been issued by African-Americans.

Citations:

Fuld, George and Melvin,

U.S. Civil War Store Cards, Second Edition, Quarterman Publications, Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1975.

Ostendorf, John,

Civil War Cards of Cincinnati, Lulu Press, 2007.

Mills, Quincy T.,

Cutting Along the Color Line, University of Pennsylvania Press,Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2013.

Lovett, Bobby L.,

The African-American History of Nashville, Tennessee, 1830-1930, University of Arkansas Press, Little Rock, Arkansas, 1999.

U.S. Civil War Draft Registration Records, 1863-1865.

Federal census for Ripley County, Ohio 1860 and Butler County, Ohio 1870.

Federal census for Davidson County, Tennessee 1860 and 1870.

The Nashville Daily Union, various issues cited above.